Non-fiction. History books. Science for amateur readers. Politics. Social sciences. Essay collections. War reporting. Travel writing. All of them and more reviewed by the Bookworm. Pulp fiction not allowed.

Wednesday, 18 January 2012

Erna Paris, Long Shadows

Oh my, ain't this book important! Long Shadows is another title that I would recommend to be a part of school curriculum everywhere in the world. But let me explain.

Erna Paris looks at some atrocious genocides perpetrated during the twentieth century: Holocaust, apartheid, Yugoslavian conflicts, Rwanda massacres and some aspects of WWII. She follows with examination of how nations as a whole and individuals react to such painful history, notwithstanding cases where the history itself is being re-forged to suit needs of whoever is in charge in a given place at given time. She philosophically explores meaning of truth, of justice and other similar fine ideas and tries to confront it with often grim realities. Important. Powerful. I wonder if also - meaningless?

It may be my own cynicism talking here, but I'm not sure if books such as Long Shadows can have any actual meaning. I, too, can ponder problems of cruelty and injustice till the cows come home, and I can come to absolutely any conclusion using different arguments, but will it change a thing? I did like the author's reporting style, I liked format of her book - interviews with many people from both sides of conflicts, with big fish and everymen on the street, I liked her going to the actual places with history of suffering to see the painful souvenirs with her own eyes. My problem, though, is this: souvenirs of pain are something very different to the pain itself. I do not believe in functionality of museums, memorials, monuments and the likes. I think it is easy to say what a bad thing genocide is if you never ever experienced this fear, if you never trembled for your own life. It is easy to preach inspired messages about conciliation if it is not your child who has been killed, maimed, hurt in mindless conflict. Long Shadows lacks anger, lacks frustration of the truly voiceless ones. I fear that armed conflicts around the world will never become less deadly unless this frustration is addressed - and yes, I am aware that it is easier said than done.

Maybe I'm being too cruel. Maybe I should simply glorify Long Shadows for an attempt to make our history less brutal, for bringing knowledge, information, focus. The book is brimming with data (not being a historian, I'm not able to say definitely if the information is objective, but it looks quite believable), with names, with figures and I respect that. There is no denying of very humanitarian spirit permeating the narrative, of deep desire to make the world a better place, to relieve suffering and do something, and this desire deserves to be praised. Yet, I am also painfully aware that it is easy to preach from the place of comfort and to condemn those, who end up in not-so-noble light because fear, pain or anger dictated their actions.

I still stick to my opinion that kids at schools should read Long Shadows. Maybe humanitarian values CAN be taught, maybe it is only my imperfect soul that asks inconvenient questions, maybe the world CAN be made a better place.

It surely needs it - and this is the main message that stayed with me after Long Shadows.

Monday, 16 January 2012

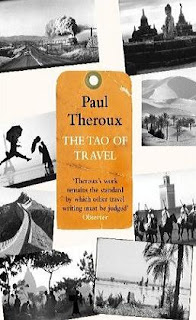

Paul Theroux, The Tao of Travel

I spotted The Tao of Travel on the library shelf because everything about this book was so NEW. It looked new, it smelled new, I've never seen or heard of it before and indeed - it was published only the previous year. Described on the cover as a collection of the very best travel writing from Theroux's own and other writers' bibliographies, it looked like a huge treat.

Guess what, I almost abandoned it after a few pages, and this is because of what I believe is the grandest structural disaster in putting a book together that I have ever seen: the first (longish) chapter consists purely of various short quotes. Let me be frank - I hate context-less quotations. A few words is rarely enough to paint any picture, to attach a reader to your vision, and I consider most such citations to be witticisms for witticism's sake. Yuck. And here I was, given a huge portion of this tasteless dish even before the dinner actually started.

It is quite possible that if this awful, awful chapter was even one page longer, I would have given up on the book altogether. Having read it through I can say now - wouldn't that be a waste! After the disastrous beginning The Tao of Travel goes only uphill. It's a pleasant combination of Theroux's own essays, memories and musings, spiced generously with (decent sized, at last) quotations from other giants of travel writing and the resulting concoction is highly digestible.

I am not a huge fan of Paul Theroux's writing style - it is slightly too poetic, too far removed from the tangible reality into fantasy worlds of his own creation for my liking, but I happily tip the hat to him anyway. I may not be much of a traveller (money...) and I certainly refuse to treat free-floating, rough riding exploration as the ultimate happiness but - how should I put it - I can honestly empathise with someone, who thinks otherwise. Through Theroux's lens, I can see why travelling may be an experience rewarding enough to be worth leaving home and risking your skin for. I can see it quite clearly.

I'm still not going to pack my suitcase and take off, and I'm quite serene in this choice, but The Tao of Travel took me not on one, but many imaginary voyages during our short acquaintance and for that I am grateful.

I even forgive Theroux the terrible first chapter.

Sunday, 15 January 2012

Geoffrey Hosking, Russia and the Russians

I've kept this book checked out from the library for more than two months. Not because it is thick - more than six hundred pages. When the mood and the book are right, I can swallow such bricks in less than two days. Not even that there is something wrong with the book. It is all right and proper as far as history books are concerned - informative, smoothly-written, explanatory.

Why, then, I couldn't bite through it for so long? Perhaps it's because the overall feeling I've had when reading Russia and the Russians was that I'm not actually reading for pleasure, but EDUCATING myself. Now, don't know how about you, dear reader, but to willingly grasp such a book I need to be either in a very 'self-developing' mood or so desperate to run away from reality into written pages that I'll read anything I can lay my hands on.

I may sound critical here but in this particular case I'm quite convinced that it's not the book that should be blamed, but my own perception, caused by absolutely non-literary matters. Anyway, here's more about Russia and the Russians:

- indispensable to anyone who happens to be interested in, well, Russia and the Russians

- valuable to anyone who wants to thoroughly understand sources and history of communism, both in theory and practice

- communism tends to be unquestioningly labelled as 'evil', but Hosking refrains from such a quick judgement. He explores utopian beginnings of the system, highlights mistakes made and generally does good job explaining why it didn't work

- overall, quite worth recommending to anyone who wants to broaden his or her general knowledge

Not very inspiring, I'm afraid, but informative.

And I am so glad I can return it now.

Thursday, 12 January 2012

Niall Ferguson, Civilization - The West and the Rest

I have to admit, I approached this book with extreme caution. Too many of contemporary works on 'civilization' prove to be a mixture of rhetoric and preaching, none of which I like. Yet I do like to embark on verbal campaigns against consumerism and shallowness of the pop culture from time to time, so I thought it a good idea to learn some more on the subject. The book was mine (for a time, that is - did I ever mention what a great fan of libraries I am?).

I have to admit (again!) I was pleasantly surprised. Of course Ferguson does suggest his own explanation for why our civilization looks like it does. I don't necessarily agree with him, but then again - it is not such a balderdash as I expected. For details read the book yourself, I can only promise you that it's worth it.

If The West and the Rest was called A Doctrinal and Economical History of the World the title wouldn't be too far off mark. Ferguson gives us skeletal histories of most (all?) of contemporary empires, presented in pleasant and quite believable way. He also remains impressively impartial throughout the narrative (in the circumstances, he can be forgiven for claiming that British imperialism was ok because it brought to conquered lands as many benefits as disasters). Sometimes it is actually difficult to guess what are the author's personal beliefs and I have to admit this is something I admire in a historian, especially when he talks about religion (which Ferguson does, among other subjects). One exception - he surely hates communism - it's the only instance I detected where his language turned rhetorical and preachy - but it doesn't take much from the book's quality.

I'm not quite sure if I agree with the author's explanation for the 'greatness' of the Western civilization or, to be precise, I'm not convinced if 'greatness' is the right word to be used here. 'Powerful', yes, 'influential' - of course. I would probably add 'predatorial' and 'ruthless' to this list and, funny thing, Ferguson's book convinced me even more that I would be right in this judgement. Regardless of whether you think that Western civilization is a blessing or a bane, The West and the Rest does a good job explaining what are the sources of its success.

Even if you don't wish to join the debate, you can read the book for the sake of interesting, little known facts with which the narrative is generously peppered. For example - did you know that most of Nazi uniforms were supplied by Hugo Boss? I didn't. That's why I'm glad I've read this book.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)