Non-fiction. History books. Science for amateur readers. Politics. Social sciences. Essay collections. War reporting. Travel writing. All of them and more reviewed by the Bookworm. Pulp fiction not allowed.

Monday, 30 July 2012

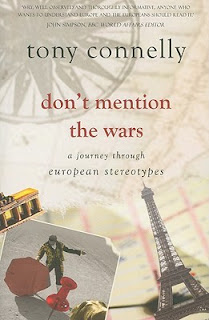

Tony Connelly, Don't Mention the Wars

Stereotyping is just as entertaining as it is dangerous. We all do it, consciously or not. Some people use it for furthering ugly agendas - politicians would be the most obvious example. Others, those with love for political correctness, claim it should be forbidden altogether - as if that was at all possible!

I bet that by now I managed to conjure a few unpleasant associations in your head, but stereotyping is not all ugly and Don't Mention the Wars is a proof.

The book is subtitled A journey through European stereotypes and this is exactly what it is. Not all the countries got invited, only Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Poland. Each chapter consists of a historical sketch and a handful of trivia organised around a central leitmotif.

Let me be frank - Don't Mention the Wars is one, big, colourful yarn. It's extremely readable, engaging and as entertaining as a book can be. I wasn't bored for a second and greedily turned page after page, devouring the book in a few hours. A fantastic read! Only... don't believe anything it says.

I kind of suspected exaggeration here and there, but only when I got to the final chapter on Poland, my home country, I could really judge the information with any certainty. Factual or spelling mistakes happen here and there, but I can forgive that easily. What did piss me off was the skewed emphasis, a tiny fragment taken from the nation's reality and blown out of any proportions. Example? You would never say this after reading Don't Mention the Wars, but Poland is full of people who don't give a damn about the Pope. I bet other nationalities could give their own examples here.

Don't get me wrong, I'm not condemning the book. I stand by my claim that it is a charming page turner, light-hearted and entertaining. Just please remember - this is a book about stereotypes, not about reality.

Thursday, 26 July 2012

Niall Ferguson, The War of the World

Do you read labels? I do. Always. It's a little quirk of mine, but one that repeatedly proves very useful. Getting familiar with ingredients list of your food or medicine can prove truly enlightening.

Perhaps it is only to be expected that I also study book covers, in detail. I'm particularly fascinated by one-line excerpts from magazine reviews. I truly admire the ingenuity of their creators. The simple, if cloaked, request (buy the book) inevitably turns into a wordy eulogy. How long can you spin a short message? I would run out of creativity - and patience! - after three raves or so. Magazine writers seem to be able to go on forever.

Niall Ferguson is a real darling of the critics, if the cover of The War of the World is to be believed. 'One of the world's 100 most influential people'. 'Niall Ferguson has transformed the intellectual landscape'. 'The most brilliant British historian of his generation...'. Proud claims, wouldn't you agree?

One word: oversell.

The War of the World is pleasant enough. It's engaging, easy to follow, accessible. Yet... I can't see how it is exceptional, much less how it transforms the intellectual landscape.

Simply put, the book is just another historical narrative covering the World Wars. I know that Ferguson tried to avoid exactly such judgement, he admits this much in the preface. As I understand, he tried to write an analysis of the twentieth century warfare, focusing on search for some general theory, applicable to all or most of armed conflicts. I acknowledge his effort and applaud the idea, but I also believe he completely failed to achieve his goal in this particular volume. With pretty much whole book devoted to the first and second global conflict and only a few chapters to the second half of the century, proportions are simply not right.

Unfortunately, I couldn't detect anything revolutionary or 'landscape transforming'. The narrative is a standard 'World Politics according to a Western historian' story. At one moment I actually wished historians were forbidden to write chronicles of their own country. Moral relativism inevitably surfaces and after a while, irks. But OK, Ferguson is not TOO guilty of this particular charge.

I also found some of his information not trustworthy. I wouldn't stake my reputation on that - after all, he's the historian, not me - but at the first sight some of his facts beg for further questioning.

So does spelling of Polish names (I was born in Poland, I know).

Truth to be told, such obvious mishaps don't surface too often and I admit I'm being picky. The War of the World is definitely readable. Not life-changing, but very, very decent.

Wednesday, 25 July 2012

Dervla Murphy, The Island that Dared

By now, I should be quite tired of Dervla Murphy, shouldn't I? The Island that Dared is the fourth book by her pen I've read now, within really short period of time and, aside from destination, the books do not really differ much one from another. They are all opinionated, colourful, controversial and absolutely delicious. I'm not tired, I want more.

What 'island' are we talking about in this case, and why is it so 'daring'? While it is easy enough to answer the first question (Cuba), the answer to the second is rather complex and you have to read the book to find it out (or possess some political knowledge gathered elsewhere). To whet your appetite, I'll tell you only that The Island that Dared is very political, but definitely not politically correct. Go, Dervla!

Cuba according to Ms Murphy might surprise you, especially if you live on the 'Western' side of the globe. It definitely surprised me, but only in an inspiring and invigorating way. Now I want to visit Cuba one day, no, 'want' is too mild a word, I'm aching to visit it. The ache will surely wear off soon, with time blurring the effects of passionate prose, but the dream might well remain.

If I ever were reckless enough to form a political opinion based on one book, I would surely became a Fidel-supporter after The Island that Dared. The Cuban (ex?) dictator, so demonised in the Western media, emerges from the book's pages almost unrecognisable. Cuba's scientific and social achievements are deservedly praised, but what strikes me most is (if Dervla Murphy is to be believed) Cuba's attitude to money. It seems that the world can still boast of places where cash is not the prime mover in individuals' life. Hard to believe, but if true - I want to go to Cuba!

A fair warning: if you are a big-time fan of corporate lifestyle, you might not enjoy this book (unless you can shrug off huge amount of criticism). Ultra-nationalistic Americans might also feel offended.

I feel tempted to say something along the lines of 'if you have any sense, you will love it', but that would be a nasty piece of mental bullying.

I loved it. You make your own mind.

Thursday, 19 July 2012

Colin Thubron, The Lost Heart of Asia

I have finally finished another one of Colin Thubron's books and I am so relieved! Can't say why, but I find his books extremely tiring. Must be my brain having problems processing all those lofty words.

Do I sound a bit sour here? If I do, let me immediately admit it might be good old jealousy. Thubron is a vocabulary master. I don't think I can even hope to ever match his skill with words. I'm duly impressed, but I also can't help wondering - are all those majestic phrases really necessary? I guess I belong to the 'if something can be said in simple words, don't complicate it' school of thought. The fuzziness of my head after three hundred pages of linguistic challenge might have something to do with it.

The Lost Heart of Asia describes countries rarely chosen as travel destinations: Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan. Thubron pretty much sprints through each, visiting main cities and meeting local people. As the book was published in 1994, it inevitably deals mainly with the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet state. Seen through this lens, all the 'stans' appear spookily alike although I'm sure much has changed since.

Even though economic realities described in The Lost Heart of Asia are rather grim, its pages sparkle with legendary names. Thubron is generous with his historical knowledge, so a reader can glimpse Central Asia as it was in its ages of glory - fierce, powerful, awe-inspiring.

I was a bit unsettled by the number of necropolises mentioned in the book. Hardly a page goes by without a grave, a tomb or at least a mausoleum being mentioned. While I realise that this land has been plagued by violent history, I'm sure there's more to it than cemeteries. Still, I could imagine a worse introduction to the heart of Asia, lost or not.

After two samples of Thubron's writing in a row I'm under impression that he is a great writer but only an average traveller. He rarely gets into trouble. He does not express controversial opinions. One feels he only skims the surface, instead of digging deep into the soul of the land he travels. Still, he is a damn good wordsmith. That's good enough for me.

Saturday, 14 July 2012

Colin Thubron, To a Mountain in Tibet

I searched and searched and I couldn't find a bad word written about Colin Thubron anywhere. One of the best travel writers in the world, says Jan Morris. One of the top fifty post-war British writers according to The Times. Whoever mentions him, does so with praise and awe.

Why, then, did his To a Mountain in Tibet leave me totally uninspired?

I AM disappointed, you know. All the applause had seriously whetted my appetite.

To a Mountain in Tibet tells a story of something akin to a secular pilgrimage. Mount Kailas is sacred to multitudes and while Thubron does not appear particularly dogmatic, he is on a personal spiritual journey. Snapshots from family life are mixed with tidbits from Tibetan folklore and politics. He meets with lamas and visits poor village dwellings, deals with Chinese officials and explores local myths.

It's not that the book is bad, or stupid, or vulgar or anything like that. Thubron's grasp of English is masterly. He takes words like 'rumbustious', 'abstruse', 'circumambulate', 'equidistant', 'coeval' and weaves them into a smooth narrative. His descriptions are poetic, his research thorough. Still, how much can you squeeze out of a short trip to the mountains?

I'm convinced that To a Mountain in Tibet is not the best book to start an acquaintance with Colin Thubron. It's fairly decent as far as travel writing titles go, but not exceptional, not life-changing, not mind-blowing. I'm going to give him another chance (review coming soon), but so far I'm not willing to join the crown of his admirers.

Tuesday, 3 July 2012

Dervla Murphy, Transylvania and Beyond

Astonishingly, Dervla Murphy managed to write a 235 page book on Transylvania without using the word 'vampire' even once. It is technically possible to explain this phenomenon by the book's publication year, 1993 being long before a worldwide fever turned vampires into a guarantee of commercial success. Somehow, though, I doubt this reasoning. Dervla Murphy does not strike me as someone eager to exploit teenage fashions. Perhaps this is why I find her writing so refreshing.

If not vampires, then what is Transylvania and Beyond about? In one way, it is a typical Murphy-esque travel memoir. What started as a holiday trip, accompanied by various misfortunes from the very beginning, developed into a fully fledged love affair with Romania in the moment of transition between dictatorship and, well, something else. Eventually, a book was born.

I have to confess that prior to reading Transylvania and Beyond I knew very little about Romania. Somewhere in the bottom right corner of Europe, capital: Bucharest, all names end with -u. As in Ceausescu. I haven't become an expert overnight, but Murphy's fascinating travelogue has added some flesh and bone to the handful of facts I had already possessed.

Transylvania and Beyond focuses on Romania's period of uncertainty right after Ceausescu's fall. Inevitably, it is full of politics. It is hard to expect a nation to think about anything else right after a revolution. In 1990 and 1991 Murphy could only try to guess what will be Romania's political future, but she was able to and she most definitely did provide a bitter-sweet image of a society just released from under a crunching regime. Bitter because poverty and suffering were only too real. Small spoon of sweetness comes from snapshots of hospitality, generosity, ingenuity enforced by lack of comforts and picturesque remnants of pre-industrial pastoral life.

I'm sure Romania is now much different than it was twenty years ago, probably much happier, too. Still, I was glad to discover this well-written, colourful account of the country's turbulent past.

Oh, I'm not done yet with my library's supply of Dervla Murphy's books. More coming soon.

Monday, 2 July 2012

Asne Seierstad, With Their Backs to the World

When I saw Asne Seierstad's With Their Backs to the World on the library shelf, I almost sprinted to grab it. What a coincidence, I've been dying to read a book presenting Balkan Wars from the Serbian point of view and here's one doing just that, written by one of my favourite conflict zone reporters.

With Their Backs to the World is subtitled Portraits from Serbia and I can't think of a more accurate description. Each of fourteen chapters included in the volume presents a different person (or group of people) telling their own version of the Serbian story. One simply cannot help being fascinated by the selection. Pretty much all political options are covered, various ways of life represented. There's a farmer, a priest, a writer, a musician, a journalist, a currency trader and a student activist. There are politicians and people who simply try to survive doing whatever they can. As much colour as it is possible to get.

Seierstad took down their stories 'in instalments', with a new update added each time she visited Serbia during the years. Thus, she managed to show how opinions and circumstances were changing with time. Some fortunes went up, some went down, other didn't really change that much. How lifelike.

I am always amazed by Seierstad's non-judgemental attitude. Sure, she does convey her personal opinions now and again, but she always does it very discreetly, by accenting a word or a sentence rather than by preaching. I also admire how respectful she is towards her sources. Inevitably, With Their Backs to the World is full of pretty extreme stories, yet she manages to withhold her judgement and refrain from condemnation. I am officially impressed.

Paradoxically, the most important observation I've made when reading With Their Backs to the World has nothing to do with Serbia, but is universal. Whatever the story, the teller is always the last to blame. Whether it's big politics or ordinary human relations, it's always 'their' fault, never 'mine'.

Funny, really.

Sunday, 1 July 2012

Cate Haste, Nazi Women

Nazi ideals and feminine graces hardly go together. Or do they? I've decided to read Cate Haste's Nazi Women to find out.

Initially, the book focuses specifically on Hitler's women - his mother (I was surprised when a photograph showed her to be a really beautiful girl), niece, early romantic interests and various female supporters. Interesting material in itself, but it doesn't really answer my question - why would majority of women of a nation support Nazism?

Further on the book's focus shifts to general population and the picture becomes somewhat clearer.

Propaganda is a powerful weapon. According to Haste, once the Nazis came to power the big brainwashing began. All the official channels projected the sparkling vision of a dutiful, healthy, child-bearing female, always ready to sacrifice her personal happiness for the sake of the nation. It didn't end with verbal promotion either - the right attitudes were rewarded with benefits and thus, better quality of life, while disobedience was severely punished. Apply this treatment from early age, continue for some years, throw in a pinch of charisma now and again - this is the recipe for mass mind control.

It seldom happjust as effective as they were eighty years ago. People are just as pliable.

Or have we learned something?ens that a book makes me physically sick, but in case of Nazi Women I had to take a break once in a while to get some fresh air. It has nothing to do with the qualities of the book itself which appears to be well-researched, with named sources and reference list after each chapter. It's the described phenomenon that is nauseating. The vision of an army of automatons, uncritically swallowing the official bullshit. Mothers proud of their sons turning into murderers, for the greater glory of the nation. Simply mind-blowing.

Worst of all, the knowledge that it did happen fills me with fear that it might happen again. Not necessarily in Germany, but in any country that puts national ideas above ordinary human compassion. Propaganda techniques are just as effective now as they were eighty years ago. People are just as pliable.

Or have we learned something?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)