Non-fiction. History books. Science for amateur readers. Politics. Social sciences. Essay collections. War reporting. Travel writing. All of them and more reviewed by the Bookworm. Pulp fiction not allowed.

Showing posts with label asne seierstad. Show all posts

Showing posts with label asne seierstad. Show all posts

Monday, 2 July 2012

Asne Seierstad, With Their Backs to the World

When I saw Asne Seierstad's With Their Backs to the World on the library shelf, I almost sprinted to grab it. What a coincidence, I've been dying to read a book presenting Balkan Wars from the Serbian point of view and here's one doing just that, written by one of my favourite conflict zone reporters.

With Their Backs to the World is subtitled Portraits from Serbia and I can't think of a more accurate description. Each of fourteen chapters included in the volume presents a different person (or group of people) telling their own version of the Serbian story. One simply cannot help being fascinated by the selection. Pretty much all political options are covered, various ways of life represented. There's a farmer, a priest, a writer, a musician, a journalist, a currency trader and a student activist. There are politicians and people who simply try to survive doing whatever they can. As much colour as it is possible to get.

Seierstad took down their stories 'in instalments', with a new update added each time she visited Serbia during the years. Thus, she managed to show how opinions and circumstances were changing with time. Some fortunes went up, some went down, other didn't really change that much. How lifelike.

I am always amazed by Seierstad's non-judgemental attitude. Sure, she does convey her personal opinions now and again, but she always does it very discreetly, by accenting a word or a sentence rather than by preaching. I also admire how respectful she is towards her sources. Inevitably, With Their Backs to the World is full of pretty extreme stories, yet she manages to withhold her judgement and refrain from condemnation. I am officially impressed.

Paradoxically, the most important observation I've made when reading With Their Backs to the World has nothing to do with Serbia, but is universal. Whatever the story, the teller is always the last to blame. Whether it's big politics or ordinary human relations, it's always 'their' fault, never 'mine'.

Funny, really.

Saturday, 24 March 2012

Asne Seierstad, The Angel of Grozny

Here's a book that grips you by the throat and kicks you in the teeth.

Grozny is the capital city of Chechnya, a semi-independent republic between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. Not exactly the place to associate with heavenly beings, just the opposite. During the last decade of the twentieth century the country was torn apart by two bloody wars with Russia. Even in the officially peaceful times Chechnya has less-than-spotless human rights record. In short - it is a violent place.

Asne Seierstad has travelled to Chechnya many times, both on 'proper' papers and in secret. She has a particular knack for listening to the stories of common folk and repeating them in a mind-shattering way. The Angel of Grozny hovers somewhere on the border between journalism and activism. Over some 300 pages it shows you a quite clear picture of Chechen-Russian relations, but it presents it through stories of ordinary people from various backgrounds.

There's one particular thing present in all the accounts - so much suffering! Such an incredible amount of useless, wasteful, unnecessary, unjust suffering that it takes your breath away. I tend to be rather cold hearted, I'm ashamed to say, too quick with cynical judgement and distrust, but Seierstad's book simply knocked me out. I kept reading fragments out loud to my partner because I simply had to share them with someone. A few paragraphs was enough to get me agitated, bursting with a strange mixture of anger, helplessness, compassion and despair. Powerful stories, powerful book.

I keep wondering if the stories should be believed. I tend to distrust storytellers - truth, after all, is such a slippery thing and words can so easily warp it. I'm still not sure. I even had an impulse to somehow contact the author and ask her - is this all true? How much colour did you add? Or is it, is it all as it is down there, in this strange country no one seems to care about? Do such things really happen, in today's so-called civilised world? Do they?

The problem is - Seierstad's stories sound so believable. All little details seem to fit. Human behaviours are pictured in seemingly authentic way. There is no black and white, but endless shades of grey and it's so... familiar. The book feels true. It might be the author's skill... But what if it isn't?

The Angel of Grozny plays on emotions. It is hard, bordering on impossible, to keep cold-headed rational judgement when reading stories of pain, torture, families torn apart, hatred, fanaticism. Some people would say this makes the book less worthwhile. I wonder.

I don't treat Seierstad's account as the absolute truth, but neither do I treat the official news as such. There is no objectivity, all stories are tailored to achieve some aims. News are coloured by propaganda and market research, The Angel of Grozny is designed to evoke compassion.

I won't use the big word 'truth' lightly. But of the two approaches to war reporting, I far prefer the latter.

Monday, 28 November 2011

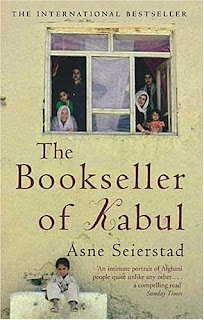

Asne Seierstad, The Bookseller of Kabul

I seemed to have made better decisions when book picking last time and The Bookseller of Kabul proves it. Truth to be told, I'm probably late by a few years with reading it - I'm dimly aware that it was a hot title during the top of Afghanistan frenzy. Nevermind, I still enjoyed it.

Books like this one inevitably make you think. I won't even start on the issue of the last Afghan war, whether it was justified or not, whether it brought more damage or benefit to the country and The Bookseller of Kabul doesn't either, not really, although it does portray wartime reality of Afghan citizens. Seierstad's novel/report (call it what you like) focuses mainly on patriarchy in Afghan society, criticising it without actually pointing the finger.

I find it an interesting literary trick - the bookseller in question is introduced as a gracious host who allowed the author into his own house etc. Nevertheless, to the western eyes the man appears rather ghastly. Nowhere in the book can you find any direct criticism, all you get is are descriptions of some day-to-day events, ranging from mundane to tragic. Still, the portrait is scary (and it didn't appeal to the man either - after the book was published, he sued the author for defamation).

If you ask me, it's not the man, but the whole society that is frightening. If the book is to be believed, women are no better than men when it comes to judging and punishing whoever happens to be of lower social status. It's the jungle law in the purest form - whoever happens to be the most powerful, issues orders and woe be to you if you dare to disobey. Victimisation of those without power is the obvious consequence, and there aren't many shelters available if you decide to rebel.

Or so it seems, because judging a society on the basis of one book seems a bit irresponsible.

Whatever the truth, the book IS gripping, thought provoking and very well written. It is an eye opening experience to read about a culture so different to ours. What I'm going to say next may not be the most sympathetic or politically correct thing in the world, but hell, let me say it - if you are a western woman unhappy with your life, do read it, if only to see that it could have been so, so much worse...

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)