Non-fiction. History books. Science for amateur readers. Politics. Social sciences. Essay collections. War reporting. Travel writing. All of them and more reviewed by the Bookworm. Pulp fiction not allowed.

Wednesday, 28 December 2011

Nadine Gordimer, Living in Hope and History: Notes from Our Century

Literary Nobel Prize tends to be a good book recommendation... but wait, didn't I say just that in my last post? I did, but Nadine Gordimer gives me a good reason to repeat it. Living in Hope and History is my second encounter with this delicious writer and I'm looking forward to reading more.

If you've read any more of this blog, you also already know that I love essays - another reason to savour Living in Hope and History. Essays collected in this book can be roughly divided into two main groups: those on writers and those on evils of apartheid (sometimes combined in the same piece). There's more than that - as it should be in works written over a few decades - but sooner or later one of the two subjects surfaces. I'm damn glad it does.

While I'm not too hot on the apartheid bit (simply because of not being very familiar with it), I fell in love with Gordimer's deliberations on writing and a writer's position in today's society. She makes the profession sound noble, more than that, she inspires writers, potential or otherwise, to strive for nobility.

'Nobility' can mean something different to each individual, but for me it has much to do with the truth, with speaking of the truth loudly and clearly, unafraid of its inconvenience or unprofitability. I spend a lot of time in virtual company of affiliate marketers presenting themselves as 'writers' and often end up bitter and disappointed under heavy showers of self-explanations these people create in defence of their profession. Then along comes Gordimer, with her powerful words on writers as speakers of the truth (whatever this truth may happen to be) even in the face of adversity and I feel like I've just been given a breath of the fresh air. There are people in the world who speak the truth even if their books are banned or burned, even if they themselves are being imprisoned, exiled, persecuted. They don't give up. They keep on repeating the politically incorrect truths because ultimately - the truth is more important, more powerful than politics. Compared to that, all marketers of the world can go hang, they are not worth anyone's time and definitely not worth my upset.

If, by any chance, you happen to be a writer struggling to oppose ever-present selling out or simply in need of inspiration, then Living in Hope and History is a must for you.

If you are anyone else, it will simply be a highly enjoyable, well-written book.

Oh, if you are a 'writer' who employs his skill in affiliate marketing, do not read it. It will only make you sad.

Sunday, 18 December 2011

Orhan Pamuk, Other Colours

If I had to pick a single writing genre that I love best, I would probably say it's essays of every shape and size. Somehow, whenever I pick a tome of essays, it doesn't much matter who wrote it. I'm happy like a guinea pig anyway. Fiction may convey truths disguised as lies, popular science may teach and dazzle, but nothing compares to musings on life, death and everything else.

Yes, you've guessed it, Other Colours is a collection of essays.

When it comes to quality of writing, Nobel Prize tends to be a good indicator of what to expect. Pamuk won the prize for his Snow, although if it was up to me, he would have got it for Other Colours. I've read Snow and I've read My Name is Red, another book of his, and although both were pretty enjoyable, I didn't devour them as I did the essays (i.e. in one sitting - all four hundred pages!). Pamuk's writing is not the easiest thing in the world, he steers sharply towards abstracts and poetry, but he sure can write.

If I was to pick one thing I liked best in Other Colours, it would be numerous glimpses of the writer at work. There are screenshots of daily routines, thoughts and motivations, in short - stuff that every writer will be familiar with. A glorious opportunity to learn from the best, dear fellow penpushers :).

To keep the balance, I also need to get picky and complain a bit about one detail that I didn't like at all - book reviews. There are quite a few literary essays, mainly concerning the classics - among others Dostoyevsky, Nabokov, Camus, Rushdie - but well... can I share one of my pet peeves with you? I totally hate it when book reviewers (even if they are distinguished and Nobel-decorated) presume to know an author's mind better than the author himself. How the hell does Pamuk (or anyone, anyone else) know what did Dostoyevsky have in mind when writing his novels? It's not as if he could ask him... Once a book is written in a language that I can understand, I don't need anyone to translate it for me further.

There, I'm done with complaining. Don't let my fussing spoil the pleasure of reading the book for you - overall it is highly recommendable.

Friday, 16 December 2011

Margaret Atwood, Oryx and Crake

I don't think like Margaret Atwood. I don't fully agree with what I presume is her world view, as expressed through multiple pieces of writing, creative or otherwise. I'm not a particular fan of poetry and Atwood's books tend to be full of it. And yet... I can't think of her in any other terms than 'one of the greatest writers of our age'.

She is good, damn good.

Oryx and Crake is her another go at anti-utopias, the world after the Apocalypse. What we get is a single survivor of a lab-generated human extinction project, trying to stay alive and musing of present and past. The story is quite engaging, the imagery extremely vivid and the vision of the future... well, not-so-impossible.

Funny enough, I didn't detect preaching. It's not a warning, at least not obviously so. It's just a story, a good one, too.

Oh, probably not recommended to underage readers. Language has not been smoothed out and well... it's not a nice story.

But if you're an adult with a taste for fine literature, do try Oryx and Crake.

Tuesday, 29 November 2011

Nicholson Baker, Human Smoke

Shocking title, shocking book. I actually chose it only because it promised 'controversy' on the cover and well - it delivered. I can't imagine any politician reading Human Smoke with pleasure... But let me start at the beginning.

Human Smoke is a World War II book. It describes years leading to the conflict and the actual war time up to the end of 1941. Yet, it is not a historical narrative, not as most people understand the term. It's a collection of press releases, diplomatic documents and diary excerpts. Baker doesn't add any commentary with his own words, he allows historical sources to speak for themselves. I'm sure he chose his material in order to create the particular picture, so his objectivity may be questioned, but nevertheless the picture is striking. I presume his sources are authentic (check some 80 pages of detailed bibliography at the end of the book if in doubt) and if it depended on me, every child would be made to read the book at school.

Popular image of the World War II tends to be rather shallow, distorted - Allies, the good guys, won the just war against evil Nazis. Hooray for our heroes, for our brave war leaders, our excellent war effort... Yet, the more I learn about the war, the less clear-cut the picture becomes. Human Smoke added a handful of new doubts to my already subversive image of the war activities. Let me share some things I've learnt:

- Germany wanted to get rid of Jews from German territory - true, and ugly too. Few people know that their first plan to achieve this was to force them to emigration. None of the 'good guys' agreed to take them in.

- the war was preceded by multiple peace initiatives, demonstrations, manifestos, publications - none of them was taken into consideration

- when people of Europe were dying from starvation by the million, war leaders (including Churchill and Roosevelt) were being driven around in private trains, fed with sirloin steaks and brandy

- speaking of brandy, Churchill did not abhor a drink during the course of his duty. Actually, he was proverbial for his love of strong liquor. It surely helped him contain aggression...

There's more, but I don't feel qualified to make public judgement based on one book (plus, I don't want to ruin your pleasure of reading it).

One thought can't leave my head after reading Human Smoke: everyone who shouts 'war!' should be sent to the front. Cheerleading a nation to a military conflict and watching it from a safe office/mansion/headquarters many miles away while unwilling children die on battlefields is not right. Whether you are a politician, a writer, a philosopher - if you vote for war, go and experience war with your own precious self instead of jailing draft resisters. Ok?

I was going to write a book review, and it turned into a political manifesto. THAT'S now good the book is.

Monday, 28 November 2011

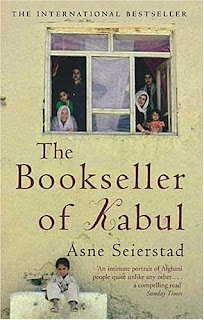

Asne Seierstad, The Bookseller of Kabul

I seemed to have made better decisions when book picking last time and The Bookseller of Kabul proves it. Truth to be told, I'm probably late by a few years with reading it - I'm dimly aware that it was a hot title during the top of Afghanistan frenzy. Nevermind, I still enjoyed it.

Books like this one inevitably make you think. I won't even start on the issue of the last Afghan war, whether it was justified or not, whether it brought more damage or benefit to the country and The Bookseller of Kabul doesn't either, not really, although it does portray wartime reality of Afghan citizens. Seierstad's novel/report (call it what you like) focuses mainly on patriarchy in Afghan society, criticising it without actually pointing the finger.

I find it an interesting literary trick - the bookseller in question is introduced as a gracious host who allowed the author into his own house etc. Nevertheless, to the western eyes the man appears rather ghastly. Nowhere in the book can you find any direct criticism, all you get is are descriptions of some day-to-day events, ranging from mundane to tragic. Still, the portrait is scary (and it didn't appeal to the man either - after the book was published, he sued the author for defamation).

If you ask me, it's not the man, but the whole society that is frightening. If the book is to be believed, women are no better than men when it comes to judging and punishing whoever happens to be of lower social status. It's the jungle law in the purest form - whoever happens to be the most powerful, issues orders and woe be to you if you dare to disobey. Victimisation of those without power is the obvious consequence, and there aren't many shelters available if you decide to rebel.

Or so it seems, because judging a society on the basis of one book seems a bit irresponsible.

Whatever the truth, the book IS gripping, thought provoking and very well written. It is an eye opening experience to read about a culture so different to ours. What I'm going to say next may not be the most sympathetic or politically correct thing in the world, but hell, let me say it - if you are a western woman unhappy with your life, do read it, if only to see that it could have been so, so much worse...

Thursday, 24 November 2011

Jules Verne, Paris in the Twentieth Century

Jules Verne has a reputation for predicting the future. You surely know at least some of his books, which tend to hang somewhere between science fiction and children stories. I've read a few and quite enjoyed them, so when I saw Paris in the Twentieth Century on my library shelf I didn't hesitate too long before grabbing it.

The book remained unknown until 1989, when it was accidentally discovered by one of Verne's heirs. It became a small-scale publishing sensation some years ago, marketed as 'the lost book' of the great writer. Is it worth the fuss?

There will be no suspense building. If you ask me, Paris in the Twentieth Century is no big deal. Easy to put down - it took me some days to get through it, because after a few pages my attention inevitably drifted somewhere else. I believe it was written sometime at the beginning of Verne's career, and that sort of redeems him... But in this case he definitely does not land on my list of the best books of all times.

One thing, though, remains typically, impressively Verne-ish - his ability to predict the future. His Paris of the future is a grim place. It is also strikingly similar to some aspects of today's reality: money is the absolute ruler of the universe.

If you want to see how joyless life is when money-making becomes priority of human kind, do read the book. As a warning.

Tuesday, 15 November 2011

Anonymous, A Woman in Berlin

I wonder how heavy a review should I write now. A Woman in Berlin certainly is a heavy book. It provides excellent food for thought. It is beautifully written. It is not for a sensitive (or underage, for that matter) reader.

A single journalist in her thirties describes her life in Berlin, spring 1945 - first besieged, then conquered by the Red Army. The diary is full of ugly details of war existence - bombardments, air raid shelters, hunger, rape, despair, uncertainty...

A Women in Berlin may provoke harsh judgements - after all it's so easy to condemn a woman, who sleeps with the enemy in exchange for food and protection. This is probably the reason why the author chose to remain anonymous and agreed to the second edition only after her death.

Germans being the official 'bad guys' of the World War II, it is rare to find the war's description through the eyes of the vanquished. It inevitably brings up questions - was this a 'rightful' punishment for the hell they unleashed upon Europe? Or a proof that the innocent suffer on both sides of any conflict?

A Woman in Berlin was turned into a movie in 2008. I haven't seen it, just letting you know it's out there.

I've consumed the book during one afternoon. Whatever else you want to say about it, it surely is unputdownable.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)